Using real-time modelling to inform the response to a diphtheria outbreak

Modelling the 2018/19 diphtheria outbreak in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

On 10th November, 2017, a suspected case of diphtheria was reported at a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) clinic in Cox’s Bazar district, Bangladesh (Finger et al. 2019). A bacterial infection, diphtheria was a major cause of childhood illness and death in the early 20th Century, before a vaccine was developed in the 1920s, then included in the WHO’s Expanded Programme on Immunization in the 1970s. In the following decades cases dropped dramatically, to the point where the disease was rarely seen in many countries. Between 2004 and 2017, there were only two diphtheria cases in the United States.

Unfortunately, diphtheria outbreaks can still occur in places that have conditions like low vaccination coverage, reduced access to healthcare, limited access to water and sanitation, and high population density. In late 2017, one such place was a cluster of several large refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar district at the southeastern tip of Bangladesh. Between August and December 2017, over 625,000 ethnic Rohingya had fled into the area from neighbouring Myanmar, settling in makeshift camps.

The site would become the world’s largest refugee camp, with evidence that there had been a long-term lack of healthcare access among these individuals. According to one survey performed by MSF in November 2017, less than a quarter of the children in the camps aged between 6 months and 5 years had been vaccinated against measles.

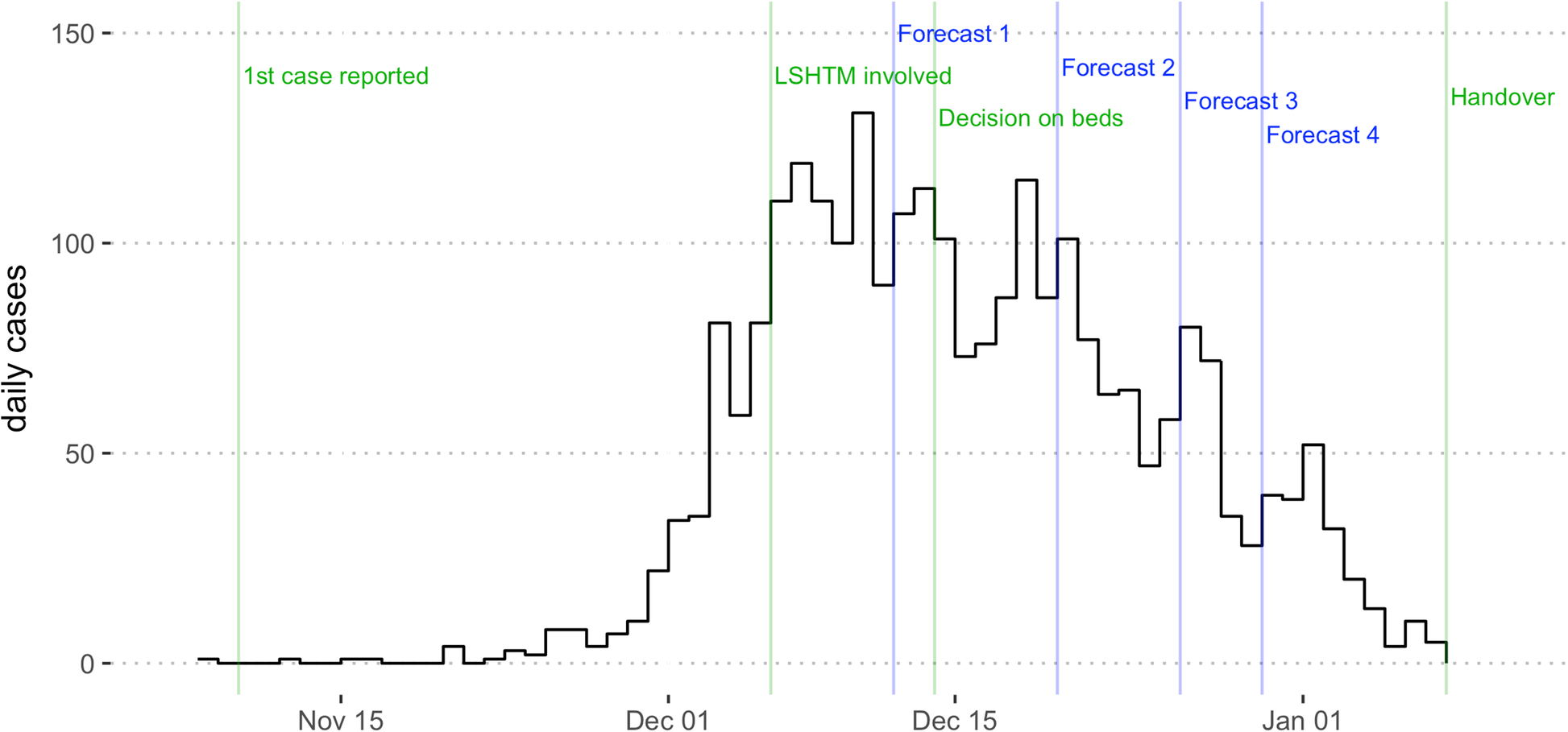

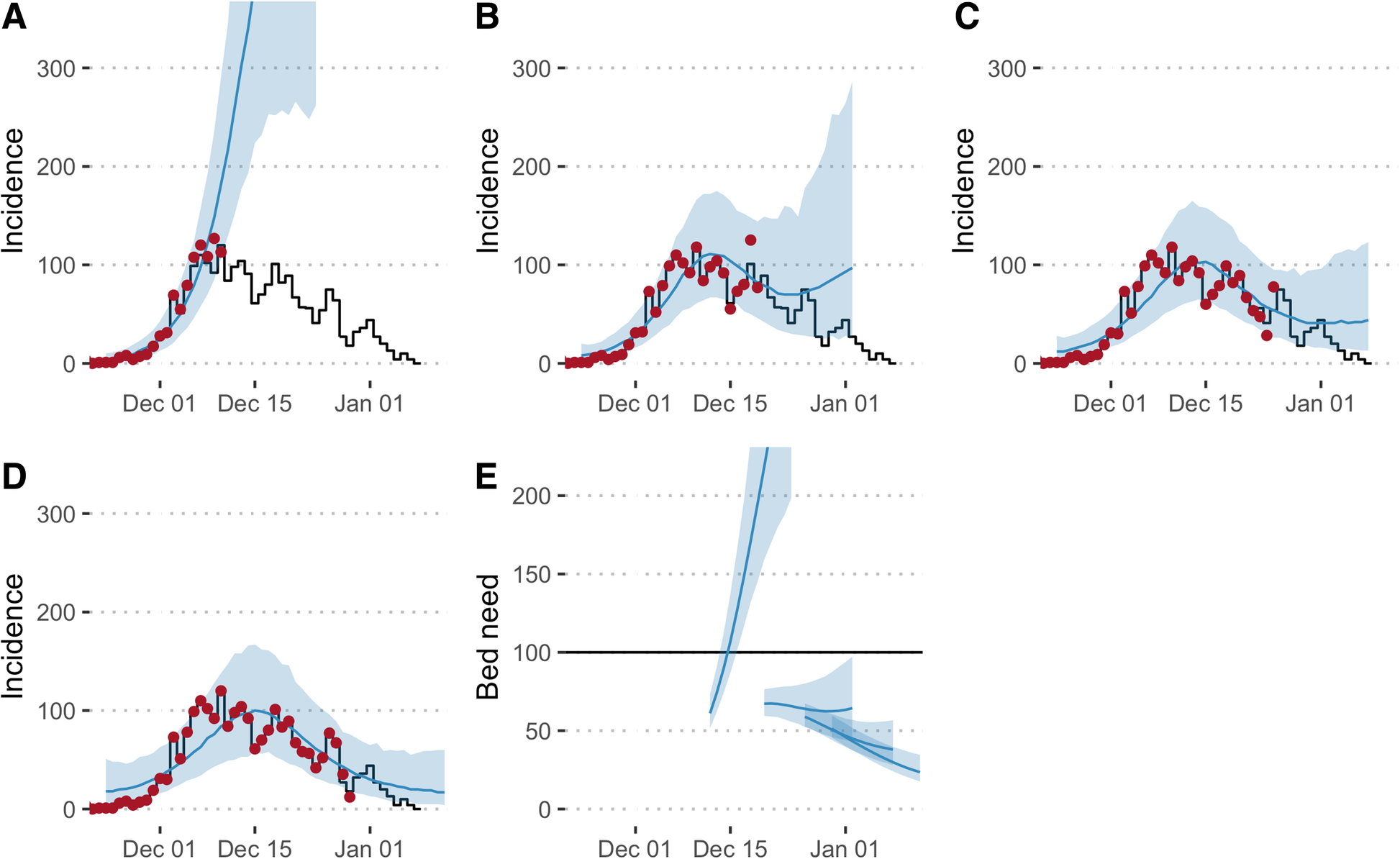

MSF had previously worked with quantitative researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) during other infectious disease outbreaks, including Ebola and cholera. When the diphtheria outbreak in Cox’s Bazar started to grow in scale, our two organisations collaborated to analyse the situation and develop analytical tools and mathematical models that could forecast how the outbreak might unfold. Our forecasts helped to inform MSF’s outbreak response plans – for example in terms of staffing and supply of diphtheria antitoxin used to treat severe cases – and to advocate for control measures with partners.

When we evaluated the performance of our models in the aftermath of the outbreak, we found that the first forecast overestimated the outbreak size, but forecasts improved dramatically in late December, when the epidemic started to slow down. This is a common challenge when forecasting disease outbreaks, and our analysis highlighted several factors that could be improved in future – such as the speed of model development and the type of model used – as well as other issues, like data quality, that are always a challenge in emergency situations like this.

Besides these technical insights, our work showed that to maximise the benefits of real-time modelling for future outbreaks, we should encourage long-term, sustainable collaborations between epidemiological modellers and the organizations working on the outbreak response. For mathematical models to realise their full potential – and to prevent analysis that is disconnected from the field-reality – communication between outbreak responders and modellers is key. This can enable modellers to appreciate the context and operational challenges involved, and help responders to understand capabilities and limitations of models.

Our study is a good example of why epidemiological analysis and modelling should be routinely incorporated in outbreak response, and for modellers to be involved at all stages, ranging from data collection, curation and analysis to intervention design and evaluation.

Building on this work, Flavio Finger spent several weeks in Bangladesh in early 2018 assisting partners with on-the-ground data analysis. He was struck by the complexity of the situation there and the sheer scale of the humanitarian crisis, but also by how relatively simple analysis of available data can help improve understanding of ongoing outbreaks – and guide the resulting response.

Note

Our article Real-time analysis of the diphtheria outbreak in forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals in Bangladesh published in BMC Medicine.

This blog post has also been published in the BMC Blog “On Medicine”.

References

Reuse

Citation

@online{finger2019,

author = {Finger, Flavio and Kucharski, Adam},

title = {Using Real-Time Modelling to Inform the Response to a

Diphtheria Outbreak},

date = {2019-08-21},

url = {https://epiforecasts.io/posts/2019-08-21-dip/},

doi = {10.59350/h07jp-s9s54},

langid = {en}

}