Workflow for Rt estimation and forecasting

Source:vignettes/estimate_infections_workflow.Rmd

estimate_infections_workflow.RmdThis vignette describes the typical workflow for estimating reproduction numbers and performing short-term forecasts for a disease spreading in a given setting using EpiNow2. The vignette uses the default non-stationary Gaussian process model included in the package. See other vignettes for a more thorough exploration of alternative model variants and theoretical background.

Data

Obtaining a good and full understanding of the data being used is an

important first step in any inference procedure such as the one applied

here. EpiNow2 expects data in the format of a data frame with

two columns, date and confirm, where

confirm stands for the number of reports - which could be

confirmed case counts although in reality this can be applied to any

data including suspected cases and lab-confirmed outcomes. The user

might already have the data as such a time series provided, for example,

on public dashboards or directly from public health authorities.

Alternatively, they can be constructed from individual-level data, for

example using the incidence2 R

package. An example data set called example_confirmed is

included in the package:

head(EpiNow2::example_confirmed)

#> date confirm

#> <Date> <num>

#> 1: 2020-02-22 14

#> 2: 2020-02-23 62

#> 3: 2020-02-24 53

#> 4: 2020-02-25 97

#> 5: 2020-02-26 93

#> 6: 2020-02-27 78Any estimation procedure is only as good as the data that feeds into it. A thorough understanding of the data that is used for EpiNow2 and its limitations is a prerequisite for its use. This includes but is not limited to biases in the population groups that are represented (EpiNow2 assumes a closed population with all infections being caused by other infections in the same population), reporting artefacts and delays, and completeness of reporting. Some of these can be mitigated using the routines available in EpiNow2 as described below, but others will cause biases in the results and need to be carefully considered when interpreting the results.

Set up

We first load the EpiNow2 package.

library("EpiNow2")

#>

#> Attaching package: 'EpiNow2'

#> The following object is masked from 'package:stats':

#>

#> GammaWe then set the number of cores to use. We will want to run 4 MCMC chains in parallel so we set this to 4.

options(mc.cores = 4)If we had fewer than 4 available or wanted to run fewer than 4 chains

(at the expense of some robustness), or had fewer than 4 computing cores

available we could set it to that. To find out the number of cores

available one can use the detectCores

function from the parallel package.

Parameters

Once a data set has been identified, a number of relevant parameters need to be considered before using EpiNow2. As these will affect any results, it is worth spending some time investigating what their values should be.

Delay distributions

EpiNow2 works with different delays that apply to different

parts of the infection and observation process. They are defined using a

common interface that involves functions that are named after the

probability distributions, i.e. LogNormal(),

Gamma(), etc. For help with this function, see its manual

page

?EpiNow2::DistributionsIn all cases, the distributions given can be fixed (i.e. have no uncertainty) or variable (i.e. have associated uncertainty). For example, to define a fixed gamma distribution with mean 3, standard deviation (sd) 1 and maximum value 10, you would write

fixed_gamma <- Gamma(mean = 3, sd = 1, max = 10)

fixed_gamma

#> - gamma distribution (max: 10):

#> shape:

#> 9

#> rate:

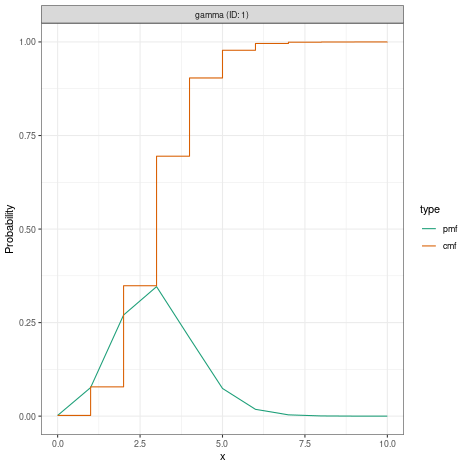

#> 3which looks like this when plotted

plot(fixed_gamma)

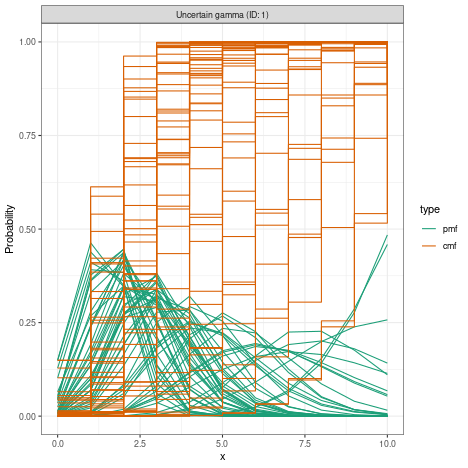

If distributions are variable, the values with uncertainty are treated as prior probability densities in the Bayesian inference framework used by EpiNow2, i.e. they are estimated as part of the inference. For example, to define a variable gamma distribution where uncertainty in the shape is given by a normal distribution with mean 3 and sd 2, and uncertainty in the rate is given by a normal distribution with mean 1 and sd 0.1, with a maximum value 10, you would write

uncertain_gamma <- Gamma(shape = Normal(3, 2), rate = Normal(1, 0.1), max = 10)

uncertain_gamma

#> - gamma distribution (max: 10):

#> shape:

#> - normal distribution:

#> mean:

#> 3

#> sd:

#> 2

#> rate:

#> - normal distribution:

#> mean:

#> 1

#> sd:

#> 0.1which looks like this when plotted

plot(uncertain_gamma) There are various ways the

specific delay distributions mentioned below might be obtained. Often,

they will come directly from the existing literature reviewed by the

user and studies conducted elsewhere. Sometimes it might be possible to

obtain them from existing databases, e.g. using the epiparameter R

package. Alternatively they might be obtainable from raw data,

e.g. line-listed individual-level records. The EpiNow2 package

contains functionality for estimating delay distributions from observed

delays in the

There are various ways the

specific delay distributions mentioned below might be obtained. Often,

they will come directly from the existing literature reviewed by the

user and studies conducted elsewhere. Sometimes it might be possible to

obtain them from existing databases, e.g. using the epiparameter R

package. Alternatively they might be obtainable from raw data,

e.g. line-listed individual-level records. The EpiNow2 package

contains functionality for estimating delay distributions from observed

delays in the estimate_delay() function. For a more

comprehensive treatment of delays and their estimation avoiding common

biases one can also consider the epidist R

package.

Generation intervals

The generation interval is a delay distribution that describes the

amount of time that passes between an individual becoming infected and

infecting someone else. In EpiNow2, the generation time

distribution is defined by a call to gt_opts(), a function

that takes a single argument defined as a dist_spec object

(returned by the function corresponding to the probability distribution,

i.e. LogNormal(), Gamma(), etc.). For example,

to define the generation time as gamma distributed with uncertain mean

centered on 3 and sd centered on 1 with some uncertainty, a maximum

value of 10 and weighted by the number of case data points we could use

the shape and rate parameters suggested above (though notes that this

will only very approximately produce the uncertainty in mean and

standard deviation stated there):

Reporting delays

EpiNow2 calculates reproduction numbers based on the

trajectory of infection incidence. Usually this is not observed

directly. Instead, we calculate case counts based on, for example, onset

of symptoms, lab confirmations, hospitalisations, etc. In order to

estimate the trajectory of infection incidence from this we need to

either know or estimate the distribution of delays from infection to

count. Often, such counts are composed of multiple delays for which we

only have separate information, for example the incubation period (time

from infection to symptom onset) and reporting delay (time from symptom

onset to being a case in the data, e.g. via lab confirmation, if counts

are not by the date of symptom onset). In this case, we can combine

multiple delays with the plus (+) operator, e.g.

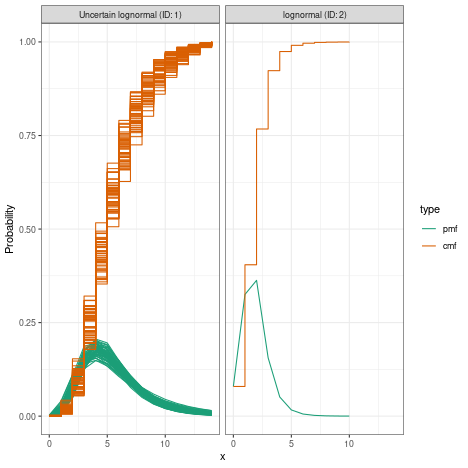

incubation_period <- LogNormal(

meanlog = Normal(1.6, 0.05),

sdlog = Normal(0.5, 0.05),

max = 14

)

reporting_delay <- LogNormal(meanlog = 0.5, sdlog = 0.5, max = 10)

combined_delays <- incubation_period + reporting_delay

combined_delays

#> Composite distribution:

#> - lognormal distribution (max: 14):

#> meanlog:

#> - normal distribution:

#> mean:

#> 1.6

#> sd:

#> 0.05

#> sdlog:

#> - normal distribution:

#> mean:

#> 0.5

#> sd:

#> 0.05

#> - lognormal distribution (max: 10):

#> meanlog:

#> 0.5

#> sdlog:

#> 0.5We can visualise this combined delay

plot(combined_delays)

In EpiNow2, the reporting delay distribution is defined by a

call to delay_opts(), a function that takes a single

argument defined as a dist_spec object (returned by

LogNormal(), Gamma() etc.). For example, if

our observations were by symptom onset we would use

delay_opts(incubation_period)If they were by date of lab confirmation that happens with a delay

given by reporting_delay, we would use

delay <- incubation_period + reporting_delay

delay_opts(delay)Truncation

Besides the delay from infection to the event that is recorded in the data, there can also be a delay from that event to being recorded in the data. For example, data reported by symptom onset may only become part of the dataset once lab confirmation has occurred, or even a day or two after that confirmation. Statistically, this means our data is right-truncated. In practice, it means that recent data will be unlikely to be complete.

The amount of such truncation that exists in the data can be

estimated from multiple snapshots of the data, i.e. what the data looked

like at multiple past dates. One can then use methods that use the

amount of backfilling that occurred 1, 2, … days after data for a date

are first reported. In EpiNow2, this can be done using the

estimate_truncation() method which returns, amongst others,

posterior estimates of the truncation distribution. For more details on

the model used for this, see the estimate_truncation vignette.

?estimate_truncationIn the estimate_infections() function, the truncation

distribution is defined by a call to trunc_opts(), a

function that takes a single argument defined as a

dist_spec (either defined by the user or obtained from a

call to estimate_truncation() or any other method for

estimating right truncation). This will then be used to correct for

right truncation in the data.

The separation of estimation of right truncation on the one hand and estimation of the reproduction number on the other may be attractive for practical purposes but is questionable statistically as it separates two processes that are not strictly separable, potentially introducing a bias. An alternative approach where these are estimated jointly is being implemented in the epinowcast package, which is being developed by the EpiNow2 developers with collaborators.

Completeness of reporting

Another issue affecting the progression from infections to reported

outcomes is underreporting, i.e. the fact that not all infections are

reported as cases. This varies both by pathogen and population (and

e.g. the proportion of infections that are asymptomatic) as well as the

specific outcome used as data and where it is located on the severity

pyramid (e.g. hospitalisations vs. community cases). In EpiNow2

we can specify the proportion of infections that we expect to be

observed (with uncertainty assumed represented by a truncated normal

distribution with bounds at 0 and 1) using the scale

argument to the obs_opts() function. For example, if we

think that 40% (with standard deviation 1%) of infections end up in the

data as observations we could specify.

Initial reproduction number

The default model that estimate_infections() uses to

estimate reproduction numbers requires specification of a prior

probability distribution for the initial reproduction number. This

represents the user’s initial belief of the value of the reproduction

number, where there is no data yet to inform its value. By default this

is assumed to be represented by a lognormal distribution with mean and

standard deviation of 1. It can be changed using the

rt_opts() function. For example, if the user believes that

at the very start of the data the reproduction number was 2, with

uncertainty in this belief represented by a standard deviation of 1,

they would use

Weighing delay priors

When providing uncertain delay distributions one can end up in a

situation where the estimated means are shifted a long way from the

given distribution means, and possibly further than is deemed realistic

by the user. In that case, one could specify narrower prior

distributions (e.g., smaller mean_sd) in order to keep the

estimated means closer to the given mean, but this can be difficult to

do in a principled manner in practice. As a more straightforward

alternative, one can choose to weigh the generation time priors by the

number of data points in the case data set by setting

weigh_delay_priors = TRUE (the default).

Estimation and forecasting

All the options are combined in a call to the

estimate_infections() function. For example, using some of

the options described above one could call

reported_cases <- example_confirmed[1:60]

def <- estimate_infections(

reported_cases,

generation_time = gt_opts(generation_time),

delays = delay_opts(delay),

rt = rt_opts(prior = rt_prior),

forecast = forecast_opts(horizon = 7)

)Alternatively, for production environments, we recommend using the

epinow() function. It uses

estimate_infections() internally and provides functionality

for logging and saving results and plots in dedicated directories in the

user’s file system.

Forecasting secondary outcomes

The estimate_infections() function works with a single

time series of outcomes such as cases by symptom onset or

hospitalisations. Sometimes one wants to further create forecasts of

other secondary outcomes such as deaths. The package contains

functionality to estimate the delay and scaling between multiple time

series with the estimate_secondary() function, as well as

for using this to make forecasts with the

forecast_secondary() function.

Interpretation

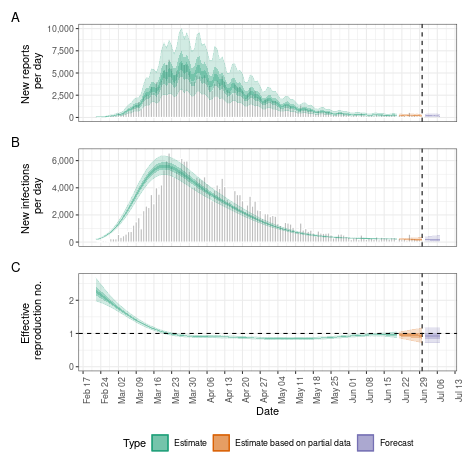

To visualise the results one can use the plot() function

that comes with the package

plot(def)

The results returned by the estimate_infections model

depend on the values assigned to all to parameters discussed in this

vignette, i.e. delays, scaling, and reproduction numbers, as well as the

model variant used and its parameters. Any interpretation of the results

will therefore need to bear these in mind, as well as any properties of

the data and/or the subpopulations that it represents. See the Model options vignette for

an illustration of the impact of model choice.

Evaluating forecasts with scoringutils

Forecast evaluation is useful for comparing the predictive

performance of different models or assessing how accuracy changes at

different forecast horizons. The get_predictions() function

supports a format = "sample" argument to return raw

posterior samples compatible with the scoringutils

package.

Since we fitted on only the first 60 days of

example_confirmed, we can score the 7-day forecast against

the full dataset. Here we show forecast scores by horizon:

library(scoringutils)

# Get sample-based predictions for the forecast period

preds <- get_predictions(def, format = "sample")

forecasts <- preds[horizon > 0]

# Add observed data

forecasts <- merge(forecasts, example_confirmed, by = "date")

# Score forecasts by horizon

forecast_obj <- as_forecast_sample(

forecasts,

forecast_unit = "horizon",

observed = "confirm",

sample_id = "sample"

)

score(forecast_obj)

#> horizon bias dss crps overprediction underprediction dispersion

#> <num> <num> <num> <num> <num> <num> <num>

#> 1: 1 -0.6505 13.31003 305.8814 0.000 190.593 115.2884

#> 2: 2 -0.8755 15.26973 657.2073 0.000 529.589 127.6183

#> 3: 3 0.2560 13.38751 190.0780 28.593 0.000 161.4850

#> 4: 4 -0.5490 13.53322 317.1630 0.000 166.370 150.7930

#> 5: 5 0.3910 13.79891 254.7470 70.291 0.000 184.4560

#> 6: 6 0.1640 13.68110 204.2124 12.438 0.000 191.7744

#> 7: 7 0.4320 13.76404 252.2392 78.715 0.000 173.5242

#> log_score mad ae_median se_mean

#> <num> <num> <num> <num>

#> 1: 7.756721 475.1733 528.5 220416.63

#> 2: 8.763339 539.6664 990.0 850682.48

#> 3: 7.476291 688.6677 211.0 87562.73

#> 4: 7.945295 643.4484 543.0 203621.15

#> 5: 7.620958 768.7281 354.5 224057.86

#> 6: 7.573535 795.4149 146.5 89926.22

#> 7: 7.522562 733.8870 363.5 246446.22